Wpisy: 5

Język: English

harlandski (Pokaż profil) 14 listopada 2015, 16:38:23

For example, it seems to be the case that with helpi, one can either use the accusative or al + nominative for the person helped. As the Plena Ilustrita Vortaro de Esperanto at vortaro.net says "helpi 1. (iun, al iu) ..." So far so good. Now let's take plaĉi. In the PIVE, all the examples of the verb are with al + nominative. But I'm pretty sure that I've heard/read phrases like "ĝi plaĉas min". I'm wondering if such a use of accusative would be considered a mistake in Esperanto.

More broadly, I'd like to ask if things are that strict in Esperanto. As I understand from my reading about the origins of the language, part of the idea was that people should be able to easily translate from their own language into Esperanto, presumably meaning that a certain amount of the native language structure would be transferred to Esperanto. So with helpi, an English speaker would write "helpu min" and a Russian or German speaker "helpu al mi", but communication would still occur. So can the same be applied to plaĉi, even if none of the examples in PIEV support "ĝi plaĉas min"?

Christa627 (Pokaż profil) 14 listopada 2015, 17:06:33

Kajto: De tiam lokomotiva vok'And songs and other poetry are known to often use unusual words and/or syntax, so that doesn't shed much light on the topic.

Min placxas kiel cxiela sono

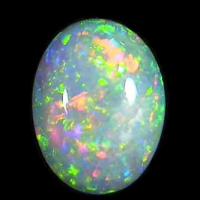

opalo (Pokaż profil) 14 listopada 2015, 17:27:36

Plaĉi is officially an intransitive verb which means "to be pleasing". Plaĉi al iu means "to please someone". It is unusual, but perfectly fine, to write plaĉi iun instead. However most grammarians insist that you can't write *esti plaĉata de.

This is discussed in § 29 of the Fundamenta Ekzercaro.

Se ni bezonas uzi prepozicion kaj la senco ne montras al ni, kian prepozicion uzi, tiam ni povas uzi la komunan prepozicion “je”. Sed estas bone uzadi la vorton “je” kiel eble pli malofte. Anstataŭ la vorto “je” ni povas ankaŭ uzi akuzativon sen prepozicio. – Mi ridas je lia naiveco (aŭ mi ridas pro lia naiveco, aŭ: mi ridas lian naivecon). – Je la lasta fojo mi vidas lin ĉe vi (aŭ: la lastan fojon). – Mi veturis du tagojn kaj unu nokton. – Mi sopiras je mia perdita feliĉo (aŭ: mian perditan feliĉon). – El la dirita regulo sekvas, ke se ni pri ia verbo ne scias, ĉu ĝi postulas post si la akuzativon (t. e. ĉu ĝi estas aktiva) aŭ ne, ni povas ĉiam uzi la akuzativon. Ekzemple, ni povas diri “obei al la patro” kaj “obei la patron” (anstataŭ “obei je la patro”). Sed ni ne uzas la akuzativon tiam, kiam la klareco de la senco tion ĉi malpermesas; ekzemple: ni povas diri “pardoni al la malamiko” kaj “pardoni la malamikon”, sed ni devas diri ĉiam “pardoni al la malamiko lian kulpon”.Basically, Esperanto is as simple as possible, but no simpler. However it can be quite difficult to notice if you are writing something ambiguous (after all, you know what you mean), which is why most people prefer to stick closely to "the rules" even when they don't have to.

harlandski (Pokaż profil) 15 listopada 2015, 02:12:40

opalo:as in English we seem to understand perfectly well when someone says "forgive him his guilt" (ie "double accusative", or at least double object with no prepositions). Here and in other cases where Esperanto seems to avoid double accusative (like "mi taksas lin kulpa" - not *"kulpan" ), I can't help thinking that "la klareco de la senco" is based to a certain degree on Zamenhof's familiarity with Russian, or other languages which also avoid double accusative.

Sed ni ne uzas la akuzativon tiam, kiam la klareco de la senco tion ĉi malpermesas; ekzemple: ni povas diri “pardoni al la malamiko” kaj “pardoni la malamikon”, sed ni devas diri ĉiam “pardoni al la malamiko lian kulpon”.

harlandski (Pokaż profil) 15 listopada 2015, 02:15:09

Christa627:The only time I recall seeing "min" with "placxas" was in the song "Melankolia Trajn-Kanzono" by Kajto:Thank you for the quote Christa627 - good to have an example of what I only vaguely remembered! I take your point about poetry not being the best judge of normal usage.

Kajto: De tiam lokomotiva vok'And songs and other poetry are known to often use unusual words and/or syntax, so that doesn't shed much light on the topic.

Min placxas kiel cxiela sono